Homeowners Insurance

The Long Tail of the Cat

Industry experts discuss how regulation is impacting the settling of claims from catastrophic events.

Rising property values and a greater concentration of people in cat-prone areas have increased insurers' costs of recovering from natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, and earthquakes.

Another element is adding to the pain of recovering from insured disasters. Catastrophe claims are taking longer to settle, with post-event costs becoming a larger share of insured losses.

A recent report from Willis Re says assignment of benefits and reopening claims on hurricane Irma caused many carriers to restate projected ultimate estimates, with loss creep eroding reinsured positions. What's driving this? Litigation, and regulators and political officials overriding the terms of coverage following a major loss.

These factors impact insurers who expect to pay what a loss is worth according to the policy, consumers who ultimately pay more for risk protection and sometimes face fewer coverage choices, and capital providers who may lack the confidence to commit financial resources to areas where natural risks are already plentiful.

A.M.BestTV spoke with industry experts about the impact of long-tail catastrophe claims on the property/casualty industry in the special program, The Cat Grows a Longer Tail.

Participants in the episode included: Robert Muir-Wood, chief research officer, Risk Management Solutions; Robert Hartwig, director, department of finance, University of South Carolina; David Sampson, president and chief executive officer, Property Casualty Insurers Association of America; Steven Weisbart, senior vice president and chief economist, Insurance Information Institute; Fred Karlinsky, co-chair, insurance regulatory &transactions practice, Greenberg Traurig, LLP; Sean Shaw, lawyer, property insurance claims, Merlin Law Group; and Christopher Draghi, financial analyst, A.M. Best.

Following is an excerpt of the special program.

Robert Muir-Wood, Risk Management Solutions

Increasingly, we’ve seen events, especially in some of the largest catastrophes, where the losses just keep rising and rising for a long time after the event.

Insurers used to view property catastrophe coverage as a short-tail line. Is it becoming more long tail?

Muir-Wood: Increasingly, we've seen events, especially in some of the largest catastrophes, where the losses just keep rising and rising for a long time after the event.

Hartwig: That's true, and increasingly so. That's unfortunate because when insurers look at how they're going to price property catastrophe business or property business in general, they make the assumption that these claims are going to be filed and closed relatively quickly.

Muir-Wood: One of the most striking examples was the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2011. I notice that even five years after the earthquake, over a six month period, at the end of 2016, the first part of 2017, the loss from that event actually went up by 10%.

Hartwig: When you have a mega disaster, there are going to be hundreds of thousands, and in some cases, a million claims or more. If you have a million claims and just 1% are in dispute, that's still 10,000 claims.

Muir-Wood: That has actually meant that it's pushed up the cost of these disasters, and in particular, it's meant that they're much more like long-tail events. The loss keeps rising for several years after the event itself has actually happened.

Hartwig: The problem here is that insurance is one of the few businesses that needs to know what its ultimate future costs are perhaps decades in the future, before they even sell the product. That's almost an impossible task to begin with, but even more so if someone is changing the rules of the game years and years after you priced and sold the policy.

Muir-Wood: This is something that if we have an even bigger event in the future, one can expect even more litigation and an even longer time for the total loss to be finally settled. This has significant implications not only for reinsurers, but actually for insurance-linked securities which may be based on a trigger designed around the overall loss from an event.

How do insurers respond when government officials change the terms of a policy after the fact?

Karlinsky: Over-regulation is one of the main concerns of not only CEOs in the insurance industry, but CEOs around the world. It is the main concern and has been for the last couple years.

Go back to the Northridge [California earthquakes] and allowing two extra years to file claims. Go to the '04 and '05 hurricane seasons in Florida and having deductibles that should have been per occurrence deductibles become season deductibles.

Then the worst example of all, really, Superstorm Sandy.

Really, it was only a superstorm to allow for the all other peril deductible, which is only $500 or $1,000 or $2,000, to be the operable deductible, versus a 1% or a 2% or a 5% deductible.

I think all these create significant problems for the one industry, the insurance industry, that does not know what the costs of its goods sold are when it initially prices its product. Let's not forget that property lines have never been considered to be long-tail lines.

We're getting to the point where if you don't know what the contract says, if you don't know what it means and how it's going to be interpreted, you really are looking at lines that should have been short-tail lines becoming long-tail lines.

It is critical that the insurers and the insurance industry get involved and explain to policy makers and regulators exactly how the pricing process works, exactly how the claims process works so that they understand that when they make a decision that seemingly has no impact, that it has a huge impact.

Weisbart: Some of the changes, like the shift to a regular deductible from a hurricane deductible is not necessarily a long-tail phenomenon. You can still settle those claims pretty quickly. The problem is the size of the claim is much larger.

There are a number of different impacts of the regulatory activity that we're talking about, some of them long-tail-oriented, but others simply creating larger losses than the policy was intended to pay for, even when the policy terms are clear.

One of the things that's happened over time is that insurers have responded to prior regulatory actions by trying to clarify the policy language. So that when a new occasion arises to apply that language, it's even less subject to dispute, one would think, than it had been at the time of the previous case.

One other thing that I think may contribute to the long-tail issue is that in today's world, social media has increased people's sense of time.

You expect the adjuster to be there yesterday, practically. There are many more opportunities for people to complain via social media that their claim isn't adjusted. Ten thousand Facebook posts constitutes a tidal wave of its own, even if that's well within the traditional time to settle these claims. It may seem like a long tail, but the pressure to settle quickly arises to some degree out of modern communications.

For a very long time, insurers have understood that when there are catastrophes, there will be claims that will take a long time simply to be reported, much less adjusted and settled. I think that was magnified to some degree last year because the three hurricanes, or the floods of Harvey and the hurricanes of Irma and Maria, happened to be so close in time that it was very difficult, if not impossible, to get enough adjusters to the places where the claims occurred.

To some extent, that just meant that people had to sit and wait until we finally got to them. You don't want to send untrained people.

The other thing to watch out in these cases is the main issue of fraud. You don't want to pay claims that you shouldn't be paying because they are illegitimate.

There are a number of factors, especially in times when these disasters happen so close in time, given the limited resources that the industry has. They're extensive, but they're not unlimited. That, I think, contributes to the struggle the industry has.

Finally, the whole question of uncertainty revolves around the idea that there will probably be some other thing that regulators will come up with. [Commissioner] Dave Jones in California suggesting that you don't need to inventory your property if your house is destroyed by wildfire. You know, just submit a claim for the whole amount.

That is contrary to standard procedure for every fire policy in America, but there they are, in effect making a different set of rules. New ways for regulators to foist uncertainty upon the industry will come up.

Fred Karlinsky, Greenberg Traurig, LLP

We’re getting to the point where if you don’t know what the contract says, if you don’t know what it means and how it’s going to be interpreted, you really are looking at lines that should have been short-tail lines becoming long-tail lines.

What's going on with litigation including assignment of benefits?

Hartwig: The normal track would be such that you would have a mega-disaster. Within six months to a year, 97%, 98% of the claims would be closed. Within one year, 99% of the claims would be closed.

This day and age, what might be happening is a slightly higher proportion might not be closed at that period of time because they've been incentivized to challenge the claim settlement, very often by trial lawyers who are, in effect, disaster chasers. They are the property equivalent of ambulance chasers who chase what would be a casualty claim.

Muir-Wood: In the 2017 hurricane season, we have seen a mounting amount of litigation take place. In the Harvey flooding, a lot of people didn't actually have flood insurance. They didn't realize they should.

There's a lot of litigation going on for those whose properties were located in the upper level of two big retention basins situated to the west of Houston. The people who built in the basins hadn't realized that they were effectively building inside a reservoir, a reservoir which only got filled up under extreme rain. There's an increased interest in mounting lawsuits against all sorts of facets of the event. In particular, in New Zealand, a lot of claims which the insurers thought they'd closed became reopened in lawsuits which were demanding that actually the compensation had not been sufficient originally.

Hartwig: What we have seen in recent years and, I would say, particularly since the era of Katrina, is an increased use of attorneys in many types of claims.

This tends to increase the number of claims that are in dispute after an event. This ultimately increases claim costs unambiguously, as would be the case in virtually any type of insurance.

Muir-Wood: There's just a lot of claiming going on. I think lawyers discovered this whole area almost 10 years ago. I think first of all in Florida, then in Texas.

Hartwig: Now we see assignment of benefits issues in Florida, which is driving up litigation costs, not just for private insurers, but even for the state-run insurer, Florida Citizens.

If you look at what Florida Citizens is talking about today, it's not the possibility of going broke from a hurricane. It is in fact that costs are being driven up by the assignment of benefits issues in that state.

Shaw: The best example is you have a pipe burst in a home. You have water pouring into your kitchen. You call someone to suck up the water. When they come, they have you sign something that's called an assignment of benefits. What that does is it puts that person in charge of your claim process.

They then submit their bill directly to the insurance company. If the insurance company then doesn't pay that bill in full, then they can come after the homeowner. When the alleged abuse has happened a lot of this work and these things are signed prior to the insurance company even getting notice of the claim.

That's something, even as someone who doesn't agree with the industry on a lot of things, that's a terrible position for the insurance company to be in. By the time they inspect, damage has happened. Costs have been incurred. The homeowner has already signed an assignment of benefits that puts the water restoration company in charge of the claim.

Something needs to change. Something needs to happen, some kind of regulation.

Sampson: Assignment of benefit abuse is rampant in Florida and is really making home ownership very difficult for working families there.

Assignment of benefit abuse is not just something that we're seeing in water damage anymore. It's also in roofs. Really, in 2017, we saw this creeping over into auto windshield replacement.

We're working with a very robust coalition in Florida to try to get the legislature to address that.

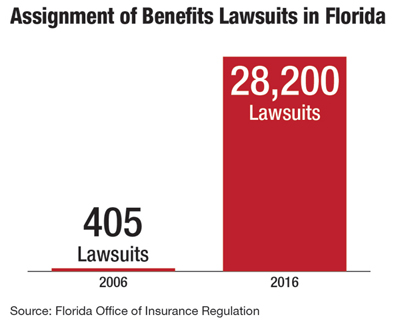

Draghi: This is a growing concern, relatively new. There's not a lot of data surrounding this. However, the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation did put out a data call study that gave us some telling information. Per the Office in 2006, there were a little over 400 AOB lawsuits. In 2016, that grew to over 28,000. You can just tell that the frequency has dramatically increased.

To give you some more quantifiable data, the frequency has increased by 46%. The loss severity has increased by 28% since 2010.

Steven Weisbart, Insurance Information Institute

One other thing that I think may contribute to the long-tail issue is that in today’s world, social media has increased people’s sense of time. You expect the adjuster to be there yesterday, practically. There are many more opportunities for people to complain.

What should the industry be doing about this increased litigation?

Karlinsky: AOB has been going on for nearly a decade in the state of Florida. I would submit to you that the '17 numbers which we didn't have crystallized are probably one and a half times what '16's numbers are.

The industry has a huge issue not with the hurricane risk that we have because I think we now understand that. We understand how to adjust it. We understand how to price for that. We understand how to reinsure for that.

I think [about] the man-made issues that we see out there. I remember when we had mold is gold, when mold was a problem. Then, you had the sinkholes, which were not really sinkholes. They were cracks and piles. Now you have AOB.

What the industry needs to do is language needs to be changed and legislation needs to be clear that this phenomenon that is affecting less than 1% of the homeowners—who in my opinion frankly are committing fraud—is impacting every single homeowner in the state of Florida through increased rates. Those things are happening in Texas and, in fact, all over the country. The insurers need to continue to get the message out.

The unfortunate thing is it's just like everything else with insurance. You can adjudicate 99.9% of your claims, great. You have 0.1%, that's a problem. All of a sudden now, the industry is the bad guy when in effect, we're rebuilding communities, rebuilding states after a natural disaster.

Weisbart: Citizens Property Insurance, which is as badly affected by this problem as the private insurers, is trying a couple of things that I think may have benefit.

They're offering an alternate way for people to settle their claims, which should be beneficial to the policyholder but also cut out the AOB problem, at least for those individuals.

If that works, I would expect that to be pretty widely adopted. I don't think that's going to solve the problem. I think it's a good weapon against what's happening.

Secondly, I think on the other side of it is that as bad as things have been in recent years, fundamentally the problems have been confined to few a counties in Florida, mostly south Florida and a little bit in central Florida. To the degree that this problem spreads to other places in Florida, it's going to get worse, not better.

I think the more districts are victimized by the use of AOB, the more representatives in the Florida House may turn to recognizing the size of this problem.

Citizens cannot pull out of Florida obviously although private companies can. One thing that the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation has been forecasting is that if this problem does not come under control, there will be companies that will constrict their writing or literally leave the marketplace.

Citizens does not have that choice. It can't raise rates any faster than the law permits. If nothing is done, sooner or later, there will be a serious financial showdown in the legislature because Citizens won't have the money to pay claims.

Not that we want that to happen but obviously something's going to have to break at that point, probably not in the next year or two, but the forces are all moving in that direction unless some major change occurs.

Karlinsky: The problem in the last couple of years has almost exclusively been in the Senate. The House actually passed a bill that would've maybe not curtailed the problem completely but certainly was a good first step. The Senate ultimately refused to take it. As a matter of fact, they did things that were, in my opinion, more likely to create AOB imputative to the insurer.

The Senate in the last couple of years has been a problem. We're hopeful that both the House and the Senate with the incoming leadership will take a much different position in that regard.

As far as Citizens, Governor [Rick] Scott in the eight years he's been in has made the decrease in numbers in Citizens one of his highest priorities because he understands that that liability is on the back of all the citizens, small c, of the state. That's a problem.

We went from a high of about 1.5, 1.6 million policies in Citizens down to about 400,000. That's creeping up right now.

That's at about 550,000 projected at the end of the year. Frankly, if we don't get the AOB problem fixed, I think that number has the potential to go even higher.

One of the problems though, that I see, is that Citizens now has so much cash. You can't really call it a surplus. But it has so much cash that it has excess that it's built up over the course of time because of its tax-exempt status that it masks the problems that are being caused by AOB. Water losses have increased 500% in Citizens, and water is the predominant cause of these AOB claims.