Active Shooter Response

Studying Options

A published, peer-reviewed study tested the effectiveness of traditional lockdown versus multi-option responses in simulations of school-shooting incidents. The results raise questions about the effectiveness of traditional lockdown.

- Cheryl Lero Jonson, Joseph A. Hendry, Melissa M. Moon

- April 2019

-

Photo Courtesy of the ALICE Training Institute

Key Points

- The Situation: Little research has been conducted on civilian response to active shooters.

- Put to the Test: Researchers studied the effectiveness of traditional lockdown techniques (hiding and keeping quiet) versus multi-option responses (barricading, distracting and swarming the shooter and escape) to an active shooter incident.

- What Was Discovered: Simulations were developed to replicate as closely as possible a school-shooting incident. Drills using the multi-option response paradigm were found to end more quickly and significantly increased the survivability of persons in active shooter incidents.

For decades, students and faculty have been taught to react to an active shooter situation the same way. Techniques include locking the door, turning off the lights, hiding in closets or under furniture and keeping quiet. In early 2000, a new approach was introduced—a multi-option response that urged victims to react by barricading, distracting and swarming the shooter or escaping the scene.

A review of the anecdotal evidence can shed light on the effectiveness of the two competing paradigms for civilian active shooter responses. The school shootings at Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook, and Marjory Stoneman Douglas indicate a failure of traditional lockdown training to mitigate casualties. Conversely, an examination of the anecdotal evidence from the shootings at Springfield, Oregon; Noblesville, Indiana; and Salem-West Liberty, Ohio suggests there is a decrease in the number of casualties when multi-option responses are utilized.

While anecdotal evidence is valuable, it cannot take the place of empirically-based scientific studies. Despite the gravity of these incidents, little to no empirical research has been conducted on civilian responses to active shooters. To our knowledge, no known ethically, empirically-based study has been subjected to rigorous peer review and accepted by a scientific journal for publication.

Until now.

In December 2018, our article, “One Size Does Not Fit All: Traditional Lockdown Versus Multioption Responses to School Shootings,” which tested the effectiveness of traditional lockdown versus multi-option responses to active shooting incidents, was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of School Violence. The study used a rigorous quasi-experimental pre-test, post-test design. While a convenience sample was used, we statistically controlled for any effect of demographic and background factors and found there were no significant impact on our results, negating criticisms of selection bias. Additionally, since one author is employed by the ALICE Training Institute (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate), multiple measures were included in the study to mitigate the influence of confirmation bias. Furthermore, to be well-qualified to study the competing paradigms, all authors participated in traditional lockdown drills and have been trained in various multi-option programs.

Anatomy of the Study

Simulation research is common and has been used to study police responses, fire responses, and crisis intervention with mental health issues. Using four simulations, the effectiveness of traditional lockdown versus multi-option responses to active shooting incidents were examined. Each of the simulations were developed to replicate as closely as possible a school shooting incident.

Individuals who were registered for a two-day ALICE Instructor Certification Course were recruited to voluntarily participate in the study and were able to opt out if they wished. Participants were given a pre-simulation survey, surveys after each simulation and a post-training survey. The surveys asked a variety of questions, including where they hid, the number of times they were shot and their background characteristics. Having participants self-report this information was intentionally done in the study to mitigate any confirmation bias. Thus, no one affiliated with ALICE filled out or assisted in filling out the surveys, and no research participant had a vested interest in the results of the study.

Simulations used Airsoft guns, protective equipment and clear instructions for all participants. The shooter, who was selected from each class and not affiliated with ALICE to further reduce any confirmation bias, was given two Airsoft pistols with clear instructions where to aim in each drill (for safety reasons, no head shots) and to shoot as many people as possible. The shooter was permitted to engage all targets for up to five minutes or until both guns ran out of ammunition. The remaining participants were assigned the role of potential victims in each simulation.

The first two simulations had participants use the traditional lockdown response. Simulations were run in classrooms first and then large open areas (e.g., hallways, cafeterias, libraries). Participants were permitted to hide in corners and under or behind desks, chairs, bookcases or other objects in the room. These simulations ended when the shooter ran out of ammunition or when five minutes elapsed. The five minute cut-off was selected to be consistent with the current data showing a large majority of mass shootings are resolved within five minutes.

After participants completed the two traditional lockdown simulations, they proceeded with the ALICE Instructor Certification course. On the second day, two multi-option response simulations were run in the same classrooms and open areas as the previous day. In these multi-option simulations, individuals were able to put into practice any or all of the options provided by the ALICE training. Evacuation, Counter, Lockdown/Barricade were labeled multi-option since the participants had the ability to respond to the shooter by choosing one or more of the options depending on their circumstances.

Unlike the traditional lockdown simulations, which all ended with the shooter running out of ammunition, most of the multi-option simulations were ended by participants swarming the shooter. There were also simulations that ended by the shooter being unable to breach barricaded areas and two that ended due to all participants evacuating the area, leaving no potential victims. This ability to choose among various options in the multi-option simulations mitigated casualties. In three of the training sites the shooter, a trained law enforcement officer, was unable to shoot any participants in the open area simulations.

Results from this study can have far-reaching implications for insurers of schools and workplaces. Underwriters and agents should seriously begin to question whether insuring single-option traditional lockdown is an acceptable practice.

Results Examined

This study examined 13 training locations across the United States for: length of time to resolution for traditional lockdown versus multi-option simulations (ALICE); the number of participants shot in each simulation; and a multivariate analysis to uncover any variables that could affect whether participants were shot in the multi-option simulations.

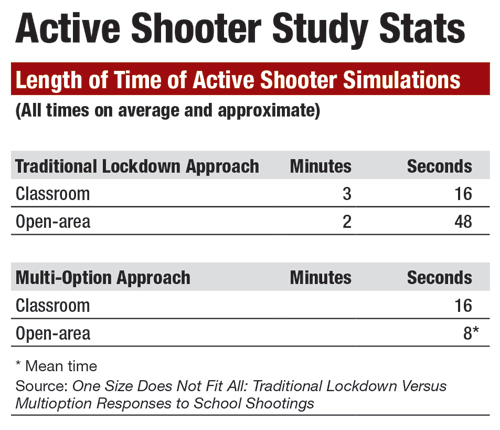

Time to Resolution: Classroom simulations requiring individuals to use traditional lockdown responses ended, on average, in just under 3 minutes and 16 seconds, while the multi-option classroom simulation ended, on average, in just over 16 seconds. The open-area simulation requiring traditional lockdown was resolved, on average, in approximately 2 minutes and 48 seconds, compared to a mean time of resolution of 8 seconds for the open area, multi-option simulation. Across our 13 training locations, statistically significant decreases in time to resolution were found in both the classroom and open area simulations for multi-option responses when compared to the traditional lockdown responses.

Percent Shot: Persons reporting being shot during the simulations showed a statistically significant decrease when multi-option responses were utilized in both the traditional classroom and open-area simulations. In traditional lockdown classrooms, on average, nearly three-fourths of individuals were shot across all training locations. Conversely, when multi-option techniques were used, on average, one-fourth of participants were shot, a drop of 50 percentage points. In the open-area traditional lockdown simulation, on average, 68% of the participants were shot across the training locations. This decreased drastically to 11% in the multi-option simulation.

Regression Analysis: To determine if the outcomes of the multi-option simulations varied by the characteristics of the participants and/or the unique properties of each simulation, multivariate analyses were conducted. These analyses uncovered that no demographic trait nor unique property of each simulation influenced the time to resolution nor the percentage of people shot. In other words, the results were not influenced by the sex, occupation, or age of the participants. In addition, the number of individuals in the simulation, the SWAT experience of the shooter, and whether a participant used the counter technique during the simulations did not alter the results.

These findings lend much credence to the effectiveness of multi-option responses over traditional lockdown. The impact of using multi-option responses does not vary by personal or situational characteristics, meaning that this approach to active shooters can be effective for men and women and those with and without law enforcement experience.

Overall, the findings of this study provide empirical evidence that using a multi-option response, and more specifically, ALICE, is a more effective approach than traditional lockdown when responding to an active shooting incident. The difference in time to resolution and number of casualties between the two approaches is stark and brings into serious question if traditional lockdown should still be considered as the sole response to these types of events.

Though this study—the first ever to empirically test either approach with live simulations—provides strong, suggestive evidence of increased survivability, it is recommended further studies be conducted with larger sample sizes, additional simulation scenarios, and varying populations (e.g., juveniles), and we welcome those studies to further the knowledge gained about these two competing civilian responses.

Nonetheless, we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge one of the main arguments of those who oppose multi-option responses. Many opponents to multi-option responses suggest children do not have the capacity to choose from various options, particularly evacuating and countering. However, two points are important to consider. First, evacuating and countering are biologically innate, which are encompassed in the fight-or-flight response to danger. Multi-option responses add one more option for individuals to choose from in active shooter situations (e.g., locking down/barricading), while traditional lockdown responses remove these biologically innate survival options and replace them solely with getting behind a locked door and hiding.

Second, other trainings provided to children embrace multi-option responses to crises. Fire training provides children with the option to evacuate, barricade (get low to the ground, close and place something under the door), or counter (Stop, Drop and Roll) depending on their proximity to the fire. Stranger Danger teaches children to run away from or fight back against a potential abductor. Thus, in other crises, the training that is provided recognizes the ability of children to choose among numerous options to increase their survivability, so why should training concerning active shooters be different?

Lessons learned from prior school shootings and various governmental reports have provided more options to consider beyond traditional lockdown. However, empirical evidence based on live simulations about civilian active shooter responses has been missing, until now. Armed with this anecdotal and empirical data, serious doubts are being raised about the ability of solely utilizing traditional lockdown as the civilian active shooter response, and a critical review of school and workplace emergency operation plans are needed. Additionally, results from this study can have far-reaching implications for insurers of schools and workplaces. Underwriters and agents should seriously begin to question whether insuring single-option traditional lockdown is an acceptable practice.

Active Shooter Options

Traditional lockdown, sometimes referred to as Code Red, was adopted as an active shooter response roughly 26 years ago according to a 1993 article in Education Week.

There are two basic responses that are being taught in traditional lockdown. One is copied from drive-by shooting drills developed in the 1980s in Southern California. This tactic involves pulling drapes, turning off lights and hiding below the window level in the hard corner, so as not to be near the door, keeping quiet and awaiting further instructions.

The second tactic is copied from earthquake drills and involves all the same tactics, except individuals are trained to hide under desks or tables instead of in the corner. These tactics are taught to be used regardless of location or circumstance, as a single-option response for students in K-12 education. This training is then brought by these same students into universities and the workplace.

After the failure of the traditional lockdown response at Columbine in 1999 to address all the variables presented during the event, Greg Crane began developing the first multi-option response, ALICE Training (Alert,Lockdown,Inform,Counter, Evacuate) in 2000. Crane concluded that traditional lockdown was not only insufficient training for active shooter events, but that it also may explain why there were so many casualties.

To read the entire study and methodology in the Journal of School Violence, visit: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15388220.2018.1553719?journalCode=wjsv20.

Best’s Review contributors: Dr. Cheryl Lero Jonson is an associate professor of criminal justice at Xavier University. Joseph A. Hendry is a retired lieutenant of the Kent State Police Department. He holds board certification as a Physical Security Professional from ASIS International and is a certified law enforcement executive and a national trainer for the ALICE Training Institute. Dr. Melissa M. Moon is an associate professor of criminal justice at Northern Kentucky University. They can be reached at jonsonc@xavier.edu.